Our latest Patients Have Power episode is called "Guinea Pigs, Backstreet Boys, Orgasms, Oh My!" (You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple Podcasts, watch the video, or listen to it with the media player above).

In this episode, I share another glass (or two - definitely two) of wine with Aaron, Clara's Head of Marketing, as we talk through common questions that patients tend to ask about clinical trials. Everything from "I don't want to be a guinea pig" to the surprising number of trials studying orgasms are discussed.

Below is a transcript of the episode for your reading pleasure!

Aaron Jun: Hello.

Lilly Stairs: Hello, Aaron.

Aaron Jun: How's it going?

Lilly Stairs: Well, most important announcement of the day is that the Backstreet Boys released a new song.

Aaron Jun: Okay.

Lilly Stairs: Why aren't you more excited? The greatest boy band of all time.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, I will agree with that. What's it called?

Lilly Stairs: It's called Don't Go Breaking My Heart.

Aaron Jun: It sounds like a cover.

Lilly Stairs: I know it sounds like a cover, it's actually not.

Aaron Jun: What did it sound like? Is it kind of rifting on current trends, is it a throwback song?

Lilly Stairs: It's just classic Backstreet Boys. Just go with that.

Aaron Jun: Well, that's great. We have a lot to get to. My favorite song by the Backstreet Boys is, "Show Me The Meaning Of Being Lonely". Underrated.

Lilly Stairs: It's an underrated song, but it's also kind of depressing.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, it is. Very.

Lilly Stairs: So, I'm not surprised that you like it.

Aaron Jun: Hello everyone, welcome to another podcast, patients at Power Podcast. We have a couple of housekeeping items today.

I just wanted to, if you're listening, we would really appreciate a five star rating. A five star rating, it's not Yelp, and you're not rating the service.

Okay?

Aaron Jun: Just rate the food, and the food is fine. Five stars would be really, really nice.

We're on YouTube now, hello. If you search Clara Health on YouTube, we pop up. If you are watching us, go ahead and hit that little thumbs up button and give us a subscribe, because that apparently also helps.

Lilly Stairs: And give us a comment, let us know. Are you drinking along with us?

Aaron Jun: We hope so.

Lilly Stairs: We encourage it.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, I mean it is ...

Lilly Stairs: I don't know if we can say that.

Aaron Jun: I know it would make this whole thing so much more fun for you. We have this amazing Patient's Have Power writing contest.

Lilly Stairs: Yes, we do. This is really exciting. Basically, we're trying to get to 100 submissions. If we have 100 people submit a blog post, which is all about demystifying clinical trials, we can help get people out of this mindset that participating in a trial means that you're a guinea pig, because it's not that.

It's so much more than that.

Lilly Stairs: The grand prize, if we have 100 or more submissions is $10,000.

Aaron Jun: It's a lot of money.

Lilly Stairs: It's a lot of money. Help us get there, make sure to submit and tell all your friends!

Lilly Stairs: You'll literally have no excuse not to be involved with the podcast. Whether you want to listen, watch, or read, you can do all of it.

Aaron Jun: And tell all your friends, of course.

Lilly Stairs: Of course.

Aaron Jun: After housekeeping, I had one piece of news that I wanted to get to before we get to the meat of what we're going to talk about.

Lilly Stairs: Okay, cool.

Aaron Jun: Today we're going to talk about demystifying clinical trials. We've helped thousands of patients, at this point, connect to clinical trials. And they've all had very common questions that they've shared.

We're going to go ahead and bust a couple of myths.

Aaron Jun: But, before we get started I did want to talk about one thing that's been kind of weighing on me and I think a lot on the patient community.

It's this renewed awareness about lobbyist, and lobbyist money in Washington DC. Especially as it pertains to the world of pharmaceuticals.

So, recently it came out that Novartis was paying Michael Cohen, who is Donald Trump's personal lawyer, $100,000 a month for access to Donald Trump, which is a lot of money.

Lilly Stairs: It's a lot of money.

Aaron Jun: Supposedly the role was for like an advisory about medicine, and Michael Cohen is not a medical professional.

Lilly Stairs: Usually lawyers don't have an MD.

Aaron Jun: Usually, and some do, but he did not. So, the $100,000 is concerning, because there are so many points of difficulty, I think, in healthcare that we want to be solving.

And this just casts a large shadow about how fair it is, not for the big pharmaceutical companies who have money. But, for the patients who get effected by the policies that come out.

Lilly Stairs: Yep.

Aaron Jun: I don't want to make it seem like it's a Donald Trump specific thing, because lobbyist money goes back decades in Washington DC across every industry.

Lilly Stairs: It's really not even just a pharma thing, because there are so many different stakeholders who are involved in drugs and pricing, and how that-

Aaron Jun: And insurance.

Lilly Stairs: Yes, right.

Aaron Jun: And all that really fun stuff. In 2017, $57 million was spent on lobbying, and that $50-ish million figure is it holds as an average for the past five years.

It's been a problem across administrations, and it's a problem now. I've been reading a lot of stories lately, courtesy of our friends at PatientsForAffordableDrugs.org.

Lilly Stairs: Which I've got it cut in for just a second to give a shout out to our Breakthrough Crew Ambassador, Sam Reid, who literally just moved from Chicago, to DC, to take a role at this organization.

Aaron Jun: Congrats!

Lilly Stairs: She's doing amazing work there, we're so proud of her. So glad to have her in the program.

Aaron Jun: That's so awesome.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: They're doing amazing work. Again, Patientsforaffordabledrugs.org. They're helping push policy, they're sharing a lot of stories. And they're stories of people who are getting affected by ridiculous drug prices and having to take out home loans to pay for their prescription drugs.

And it's just not equitable, it's not fair. I think getting involved, all of us, who work in this field, getting involved and making sure that we ensure that everyone is aware that this is not okay. And that we know what's going on.

Aaron Jun: I think that's going to yield some better outcomes in the future. I hope that everyone visits, checks them out, and maybe even donate a couple of bucks.

Lilly Stairs: Absolutely. Awesome, well thanks for bringing a little bit of hot topic healthcare into the conversation.

Aaron Jun: It's a hot topic, I think.

Lilly Stairs: Oh, it's definitely a hot topic.

Note: We don't mean this hot topic.

Lilly Stairs: Let's get to the meat of our conversation today, which we use this phrase, "demystifying clinical trials" a lot.

But, I think we want to do today, which is a little bit different then what you might see when other people talk about clinical trials, is actually discussed some of the most frequently asked questions we get because like you said, we chat with thousands of patients. We have chatted with thousands of patients.

Lilly Stairs: We have all of this data that we've collected about, what is it that people are Googling? This morning, I'm all hopped on WTFix from the conference this morning.

But Mette, our good friend at Mette, over at Mymee, was talking about how you need to build and design something for people's Google persona.

What's your Google persona? What are you typing into Google.

What are the questions that you're writing? Because that's who you should be building for, because that's what you really truly feel. We have been starting to unearth some of those Google personalities and profiles to understand what patients really actually want to know when it comes to clinical trials.

Let's talk about it.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, let's talk about it.

Lilly Stairs: Before though we really dig deep, I want to a moment just to talk about clinical trial phases, because I think that's such a critical part in all of this. I want to make sure that's all laid out.

For those of you who already know this, sorry, but it's a good primer for the rest of the conversation.

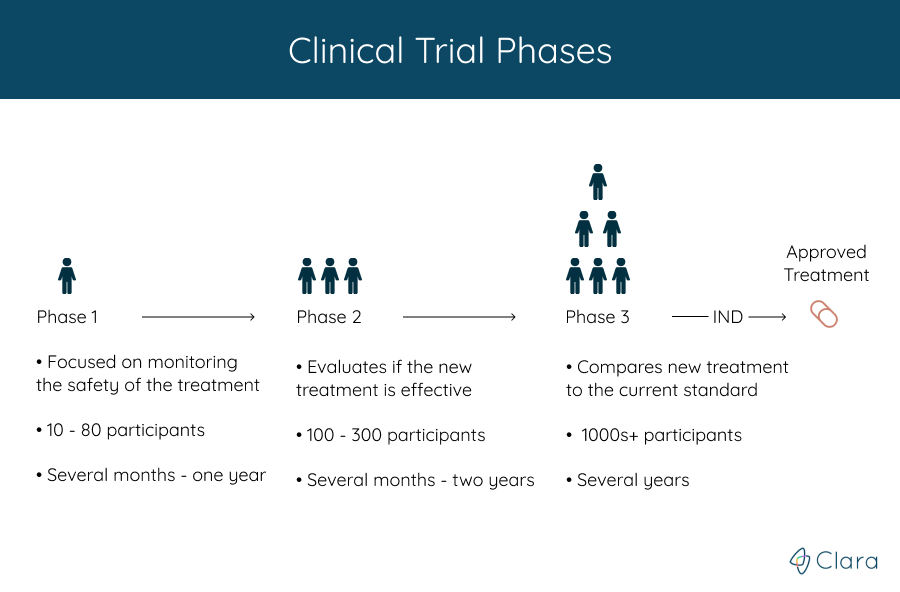

Lilly Stairs: There tends to be four phases when we're talking about clinical trials (forgive me, because I don't want to tell you the wrong thing. I'm going to look at my cheat sheet).

Phase one, this is going to be small. You're going to have generally healthy participants. 10 to 80 participants.

Lilly Stairs: That's going to go a couple months to a year long. Okay? That's pretty early on.

Phase two we're going to add more participants, go into the 100's of participants. This is going to go from a couple months to two years, and you are going to actually start to see at this point that you're evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment.

Lilly Stairs: So, in phase one you're just looking at safety. Now, we're going to start to look at safety and effectiveness.

Phase three is the phase that we get to before we are actually would go to approval. In phase three, you're going to compare the new treatment with whatever the current standard of treatment is, if there is one. This is going to be thousands of participants, over the course of several years.

Aaron Jun: Right.

Lilly Stairs: Phase four, surprise! There's one after the drug gets approved, or the treatment gets approved. That's to monitor the long term, the safety and efficacy of drugs. Anyways. That's just a brief overview of the phases. We do have more information on that on our website if you want to dig deep.

Lilly Stairs: We're going to be referencing the Clara Guides. (You can find that at guides.clarahealth.com).

Lilly Stairs: Yep.

Aaron Jun: One thing I'll add about the phases and the timelines about the phases, several months to a year, several months to two years. Several years.

A lot of that slowdown actually comes from the fact that it's really hard for researchers to get patients to participate.

There's a disconnect that folks like us are trying to help solve.

Lilly Stairs: Yes.

Aaron Jun: Hopefully, by beginning to demystify some of this stuff, and have open conversations about common fears, or common hurdles, we're going to be able to accelerate some of this timeline.

Lilly Stairs: When we say that this is a struggle, we mean it. It's over 80% of clinical trials that are falling behind because they cannot get enough participants.

A lot of that is due to lack of awareness, and due to the stigmas associated with clinical trials.

Lilly Stairs: One of the first things I want to tackle today is this safety idea. This idea of safety is the number one phrase I hear.

Aaron Jun: I don't want to be ...

Lilly Stairs: A guinea pig.

Lilly Stairs: You know, it's so funny because even when I'm talking to people who are not a patient, they're not looking for a trial, I'll explain what I do. And they're like,

"Oh. You just help people be a guinea pig."

Lilly Stairs: No! That's not what we're doing. Then I have to try and explain all of that. Why do we believe you're not a guinea pig? We've got a lot, just hear them.

Aaron Jun: So, before anything can happen around human participation there has been years of work, and years of testing.

Lilly Stairs: And they're testing on real guinea pigs. Right? Real animals.

Aaron Jun: If you want to make it really dark.

Lilly Stairs: I'm sorry, it is a little graphic. It is sad. But, they do testing on animals on it before they do with humans.

It's gone through quite a bit of safety, precautions, before it's actually getting to humans. And the biggest trials with humans are phase three.

Lilly Stairs: You've already gone through phase one and two testing with humans.

Aaron Jun: Sure, right. I think there's a common misconception around - maybe pop culture presents clinical trials one way - I think when I came into the field, I don't come from health care or health tech.

When I came into the field, the first image that came to my mind was Dr. Frankenstein heckling over the body of his little monster, with the lightening bolt.

Aaron Jun: I think that's actually how we think of research a lot. It's just like mad scientists in a weird garage, or a lair somewhere just cackling over something really, really morbid.

Lilly Stairs: I mean, it couldn't be further from the truth, because time and time again we hear from patients who have actually participated in trials that it's the best care they've ever received because they have to be so closely monitored and watched. And, they have a care team who is very attentive, making sure that everything is lining up right.

You know, another thing about safety that I'll flag is selfishly on the researchers part - and I don't blame them for this - they're really only wanting to admit patients into these trials who are going to be set up to succeed.

Right?

They're going to benefit from the drug, and they're going to do well on the drug or the treatment - because they need to show good numbers for that treatment to be approved.

They're trying to pick patients who have the best profile to thrive on the treatment that you're getting.

Aaron Jun: I think we could tell you from personal experience of helping so many patients try to connect with clinical trials that it's not easy.

Lilly Stairs: No.

Aaron Jun: It's not easy to enroll in one right now. A lot of that is because of extremely strict criteria. I tell you, we work with some pharmaceutical companies to help them understand how to be patient centric and how to recruit in a more modern, friendly way. We come up, time and again, with this thing called an IRB.

Lilly Stairs: The IRBs. I know they do good work.

Aaron Jun: They do good work.

Lilly Stairs: But, boy are they frustrating.

Aaron Jun: The Institutional Review Board, the IRB, they're a bunch of professionals with diverse experiences and research medicine, ethics. And they review every clinical trial.

No clinical trial in this country can run without the strict approval process of an IRB.

Lilly Stairs: Right. And each trial has its own IRB that's composed of different people who are equip to report back on what exactly that trial was studying.

Aaron Jun: I'll tell you, it's not just what the trial is studying. It's, let's say, I want to change a sentence in my trial listing on clinicaltrials.gov.

Lilly Stairs: Or Clara Health.

Aaron Jun: Or Clarahealth.com. To make it easier to understand, if I at some point after my IRB process want to change one simple sentence, keeping the original meaning intact. Taking out maybe one verb and substituting in another.

I need to call my IRB again, go through the cost, hassle, and time of engaging with the IRB and wait for approval, which can take weeks.

Lilly Stairs: This applies to every single piece of content, every communication that happens, from the patient to the trial site.

It is rigorous.

It is to ensure patient safety, to ensure that ethics are at play here. We recognize all of that. I guess you can have peace of mind that that means you're probably getting a pretty safe deal.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, it's been tested. It's like a car. You're not getting in a car in the 21st century without trample zones and air bags.

Lilly Stairs: Those are some of the conversations that I wanted to bring up around safety. That's definitely one of the myths. There's so many other myths that we definitely encounter when it comes to clinical trials, things that people chat with us about.

One of them being placebo's as well.

Lilly Stairs: I don't want the sugar pill, I don't want a placebo. That's what we hear. We understand, and guess what?

Clinical trial design understands too.

The fact of the matter is that now, they're moving away from the placebo, meaning the placebo sugar pill and actually moving towards what is known as the standard of care.

Lilly Stairs: When you are entering a trial, you are either getting the new treatment - ideally. You're either getting the new treatment, or you are getting the current standard of care, which means the current approved option, the FDA approved option that is the go to that physicians will prescribe.

That's what the control group is getting. Not a sugar pill. You are still getting treatment, because IRB's (our new favorite group of people), they will not allow a trial to happen if it would be unsafe for a patient to be on a placebo sugar pill.

Aaron Jun: The easiest way to understand this is, you could imagine a cancer patient going into a clinical trial. And there are so many clinical trials for cancer patients.

Lilly Stairs: On a side note, this morning we heard from Bryce Olsen at the WTFix conference that only 4% of cancer patients are enrolling in clinical trials - which is really a shame.

We can talk more about that later, but continue your train of thought.

Aaron Jun: My train of thought departed me.

Lilly Stairs: I've ruined it.

Aaron Jun: No. You can imagine that giving a cancer patient sugar pills will just yield really, really bad results for that cancer patients. It's not done, it's not palatable to any of these researchers, nor to their IRBs - even if they wanted the researchers wanted to get sugar pills out for some strange reason.

That is a common fallacy that gets designed out of the process, and it just does not happen.

Lilly Stairs: Right. Right.

Lilly Stairs: Along these same lines here, we've talked about placebo, and I just mentioned Bryce who spoke at WTFix this morning. But, another myth is that clinical trials are a last resort.

Lilly Stairs: You only go to them if this is it. You've tried everything else, there's nothing available for you. What I found really interesting this morning was that this gentleman Bryce, who has cancer, he had his genome sequenced. He has been using precision medicine to guide his decisions and what he does.

Lilly Stairs: He said he's been - his term was "coasting", on clinical trials for the past couple of years, because he said these clinical trials are giving him access to cutting edge therapy.

They are ultimately better, they're more personal and personalized to him as opposed to what is currently on the market.

Aaron Jun: Right.

Lilly Stairs: That's what some of these therapies in trials are doing. We see this not just in cancer, but in things like autoimmune diseases. We talk about this a lot. We know how biologics you can build up anti-bodies. Not every biologic mechanism of action works for every person.

Aaron Jun: Mm-hmm.

Lilly Stairs: Perhaps the ones on the market aren't the right fit for you, but the ones in clinical trials with a different mechanism of action could be a fit.

Aaron Jun: Yep. One myth that leads into this myth is the fact that a lot of doctors aren't mentioning clinical trials while their patients are at their office.

It's such a simple reason, and it almost sounds ridiculous when you say it out loud - but not every doctor in the world is going to be aware of every single clinical trial.

Lilly Stairs: Well, how can you blame them?

Aaron Jun: Right.

Lilly Stairs: They don't have the time.

Aaron Jun: Yeah.

Lilly Stairs: We talk about this, how they have ten or less minutes to see patients when they're double, triple, booked. They don't have time to keep up with every trial that's happening at every hospital in the world.

Aaron Jun: Right.

Lilly Stairs: Patients will often come to us and say,

"If this is an option, why hasn't my doctor told me?"

Because we, in our society, we look to doctors as this almost God like figure and that's changing. We're trying to help steer that movement of the Patients Have Power movement, that you have the power to control your journey and to make treatment decisions yourself.

Lilly Stairs: It's interesting, that. Unfortunately, it's not always brought up in a physician's office. But, that's why we're here. We're here to put this power into the hands of the patient, so that they know it's an option.

Aaron Jun: I think what we've noticed in the 21st century is that everyone Google's everything.

Lilly Stairs: Dr. Google.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, Dr. Google. We just moved to San Francisco. I was buying a new garbage can for my apartment.

Lilly Stairs: Very sexy.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, right? I got this awesome under counter thing, it's great, it looks awesome.

But, basically, I would have bought this garbage can from wherever I saw a garbage can five years ago. But, because I have all this information on hand, I felt this empowerment. I know it sounds ridiculous, but it was empowerment to spend three minutes searching "best, small garbage can, for small apartment".

Aaron Jun: There was a huge amount of literature, I think what we're seeing now is that patients are getting access to content that is tailored to them, and spoken in the language that is approachable for them. I think researchers and folks from the industry, like us, like pharmaceuticals, like whomever.

I think they're realizing that it's okay to speak in the language of the patient, you're not talking down to the patient by not using these complex scientific terms.

That you're actually making it more approachable for patients, and that by making it more approachable, patients are more excited, enthusiastic, and ready to engage with whatever you want to provide them with.

Lilly Stairs: Sure - clinical trials, they really don't have to be this big scary thing. There are all these really fascinating clinical trials that you probably didn't even know existed.

There's one where, literally, I kid you not, go to Clarahealth.com, search for trials. Look under keywords, type in "orgasm". Clinical trials will come up.

There are clinical trials happening in this space. I bet you never guessed that.

Aaron Jun: No. No, I didn't.

Lilly Stairs: But, what I'm saying is that all of these things need to happen, right? To move forward, and to drive research. There are natural history studies, there are observational studies.

I was reading about one that was looking at siblings, where one has rheumatoid arthritis, but the other doesn't. Why is that? Why is that happening?

Lilly Stairs: It's not interventional, it's simply, actually, just monitoring. There's a lot out there, and there can be something for everyone.

Aaron Jun: I'll plug one other thing along those lines.

Lilly Stairs: Sure.

Aaron Jun: The NIH is doing this amazing, really widespread study called "All of Us". Basically, they're trying to enroll a million people into their study. It's an observational study.

Lilly Stairs: You posted about this today, but I didn't read it.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, I know you didn't. I've been posting a lot lately, and Lilly doesn't read any of it.

Lilly Stairs: That's not true, I read some of it.

Aaron Jun: She doesn't read any of it.

Lilly Stairs: You don't read what I post.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, it's besides the point. This study, what they're trying to do, is they are actually trying to recruit an equal representation of people and across a huge spectrum, and a huge number of them.

They actually talk very specifically about the need for minority representation in clinical trials.

Lilly Stairs: Huge, it's so important.

Aaron Jun: Obviously, we'll do a podcast on this. I've been researching a bit. It's a really complicated, messy, horribly sad history of the way testing was done in the past on minority populations.

Lilly Stairs: Right.

Aaron Jun: But, that carries over from generation to generation. That leads to healthcare that's not equitable.

We live in a society right now, in America, in 2018 where black women die three times more frequently in child birth than white women.

Lilly Stairs: Really?

Aaron Jun: Yeah. It goes from everything from physicians not understanding how to interpret the way black women are stating their pain. There's been studies that show that physicians are more likely to underestimate the level of pain a black woman is experiencing, compared to a white counterpart.

We live in a society where none of this is equitable, yet.

Aaron Jun: It's really cool to see these clinical trials happening that are trying to level the playing field a little bit so that maybe a generation from now, there's a little less fear and more equity across the board.

Lilly Stairs: Sure, yeah. Really, that's great. I'm glad you brought that up. We went off talking about all of these awesome different clinical trials and we'll definitely dig deeper into those in episodes so stay tuned.

But, I want to get back into talking about what some of these big FAQ's that we get are.

Lilly Stairs: Another one is cost. "Do I have to pay for this?" Most of the time the answer is no. Most of the time. The treatment is often free, it's covered by the sponsor or the pharmaceutical company who was running the trial. Even in travel, if they are what we like to call a patient-centric trial, and they have thought about their design, they will pay for you to travel.

Unfortunately, a clinical trial doesn't run at every single hospital in every single state across the country. But, if there is a trial happening that could be a fit for you, and you are willing to travel there, they might cover air fare, hotel, Ubers, Lyft, whatever your preference is. They'll cover all of that for you, which is really amazing.

Aaron Jun: You can imagine their priority is in recruiting as fast as they possibly can because all of this research takes tremendous amounts of R&D money. Losing a day can mean quite a bit on a balance sheet.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: Whatever it takes for them to recruit and make patients feel comfortable, they are largely willing to do it.

One thing, on this, that I find fascinating is the old standard of opening a clinical trial has been "I'm recruiting for rheumatoid arthritis, and I know that MGH (I don't know if this is true) in Boston has the best rheumatoid arthritis department or a doctor, and they have the best population of patients. I'm going to open up a site there.

So, they open up a site expecting to recruit 20 patients. But, they never do, because that's not how it works. Then they go, okay, the second best site is in UCSF in California. They open one there, and they're like, I got to get 25 here. And they get 5.

They do this over, and it costs tremendous amounts of money.

Lilly Stairs: Millions.

Aaron Jun: Millions and millions of dollars to do this and they lost a whole lot of time.

What we're finding now is that some of the younger pharmaceutical companies, or some of the more patient-centric pharmaceutical companies are actually looking at where patients are kind of raising their hand and saying, "I'm available. I would like to do this".

And they are like, okay. They will open a site near the patient to cut costs, cut time, and move faster.

Lilly Stairs: I will tell you, this is a side note. I think when you say "younger", and I'm going to champion the millennials for a minute because we talked about this this morning, again, at the #WhatTheFix conference is that millennials are actually, seemingly, much more in tune with patients and patient empowerment.

We're seeing that actually with physicians as well, and younger pharmaceutical companies as well as physicians. Yes, this idea that power should be in the hands of the patient. I have to imagine a piece of that is that these millennials to a certain extent have grown up with the internet and social media, and understand the power of the consumer.

Because ultimately, patients, whether they choose to be or not end up being health care consumers. Anyways, that was just a side note.

Lilly Stairs: Okay, so another piece is also travel. We do, and we mention that travel will be covered, often times, if it's a patient-centric trial. But, understanding, okay, what if I don't live 10 minutes, 20 minutes away from the trial, can I participate?

Often times, again, you can. That's just an important thing to know, again, something we get a lot of questions about.

Aaron Jun: I'll cut in here to say that, again, some pharmaceutical companies are coming along, and some pharmaceutical companies will eventually come along on this train.

I think a lot of people don't seem to understand that patient journeys are actually not that unique. I think we think of health journey's as very unique, and they are to some extent.

But, the concerns that get shared among people are not that unique.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: "I have a child. And now you're asking me to drive 300 miles. I can drive 300 miles, but I have a child. I have a dog, can I walk my dog? How am I going to get the time off of work?"

Aaron Jun: I think what has happened is we think of health journeys as unique, or we don't think of them at all. And we end up not designing for just everyday human concerns.

All patients are human.

Lilly Stairs: That's a great point, yeah.

Aaron Jun: They share the concerns of "I'm hungry, I'm thirsty, and I have a child, and I have a dog. I want to go on a date."

I think it's been really nice to see that working with some pharmaceutical companies, seeing that they are cognizant of this, and trying to do things like, "Okay. We should actually just open up a bunch of small sites near your patients. We should allow them to take Ubers, we should do this, we should do that."

Lilly Stairs: That's a good point. Some trial sites will - depending upon how rare disease is - some of them will open trial sites near where a patient is.

Aaron Jun: Yeah, exactly.

Lilly Stairs: Which is really incredible. I think we've been lucky to work with some really patient centered companies. For those that maybe aren't as patient centered, we're trying to push them in that direction.

Aaron Jun: Right, we'll get there. We'll get there.

Lilly Stairs: I think one of the last points I wanted to talk about as it relates to frequently asked questions is EHRs - Electronic health records.

Aaron Jun: You just had an experience with electronic health records.

Lilly Stairs: Okay, they are wonderful in many ways. I think we've got a long way to go on some of this technology, I will say that. I'm excited about a lot of the start ups in this space who are trying to disrupt it because God knows we need it.

But, I actually have been working with a company to crowd source, basically, all of my medical records from various hospitals over the course of my life.

Aaron Jun: And you've been to a fair number.

Lilly Stairs: I don't even want to get into how many I've been to. And trying to remember all of that. I sent all that in, I need to send the names of the doctors that I could remember, and then the facilities and what not.

They took some time, and they get it all for you, so that you don't have to deal with it - which I will say is a huge benefit because freaking trying to call these hospitals and asking, "Okay, can you send me these medical records?"

It's not easy.

Lilly Stairs: Press one to do this, press two to do this, press three to do this. And then you call, and you wait, and you wait, and you wait, and then you talk to somebody and they're like, "Yeah, okay. What do you want? We can maybe send that, we can't send this."

They go in, and they do all of that heavy lifting for you. I got the medical records back, which was really great. They have them all compiled from all the different hospitals. But, they still did not even capture everything. Right? Some of the most important things that I have in there are capsule endoscopies, which confirms my Crohn's diagnosis - and that was completely missing.

That was because they didn't have every single physician listed that I had seen. I had gotten a capsule endoscopy when I was in the ER. If you'd like me to try to remember the 5,000 doctors that came into my room when I was in the ER and on 90 mg of morphine, good luck.

Aaron Jun: I don't know, maybe an McSteamy was in there McDreamy...

Lilly Stairs: If only!

Aaron Jun: I mean, it is really hard. I can't imagine, because you've been to so many more doctors. Luckily, I haven't had too many issues in my life.

Lilly Stairs: Debatable. I think you have more.

Aaron Jun: I have no health issues whatsoever, as Lilly just said. I have nothing wrong with me. Even I can't remember the three doctors I've seen in the last seven years.

Lilly Stairs: Right. So, what happens is, for clinical trials, patients do need to often send their electronic health records, which makes sense because they need to understand your medical history. They need to make sure there is going to be no issues with the treatment, because you've had something happen to you in the past.

Patients will say, "I don't know." It's a barrier of entry of getting into a clinical trial because patients will say, "I don't know how to do that." or "I don't know how to get them." "I can't access them."

Lilly Stairs: Can you blame them?

Aaron Jun: My parents call me all the time about their wi-fi being slow, and my dad, he's a nuclear physicist. My advice all the time is "have you unplugged it? Do you know?"

Now we're asking people who might not have tech literacy up to a certain standard.

Lilly Stairs: And are sick, and not feeling well.

Aaron Jun: And are sick, and have, again, all these other concerns I their lives. Like, we have a dog. They need to walk the dog.

Lilly Stairs: Why can't they have a cat? I'm just asking.

Aaron Jun: I mean, they could have a cat. But, my dad finds them creepy, and so do I. That's besides the point, that's besides the point.

I think it's an unfair burden, but one way that patients can get ahead of this is just understanding that this is going to become more and more of a requirement, right?

Lilly Stairs: Right, right. It's something that, at Clara, we actually help patients get access to their medical records. We'll do some of that heavy lifting on that side of things. When you can find people like Clara, I mean our giving ourselves a plug but I should because we're pretty great.

Lilly Stairs: But, if you find other organizations who can help you with these things, that's great. That's really wonderful. We're one of those people who is trying to take the burden off of the patient. But, I know there's a lot of different people out there.

Whether it be clinical trials, or just general coordination of care. There's a lot of resources.

Aaron Jun: I think it's going to be a very exciting like two to five years.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: Health tech, it took a while. When I used to life in San Francisco, before we moved back once upon a time it was 2010 when I moved here.

Lilly Stairs: You're so old.

Aaron Jun: I know, I'm so old. When I used to live here, the joke was, when you need a cab, you won't get a cab. If you were out in the Richmond, then you need to get back to Russian Hill, you would be stranded if you missed the last MUNI.

Lilly Stairs: Did you ... You just used a lot of words that are San Francisco specific.

Aaron Jun: If you're in one neighborhood and you live somewhere far away, and the buses stop running, it's hard to get back home. And that's the way it was for everybody, right?

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: I came back to San Francisco in the winter of 2012. And all of the sudden Uber and Lyft had gotten through a huge uplift in their usage. Now, I see Lyft and Uber everywhere. And I'm fascinated, right?

Lilly Stairs: It takes two minutes to get an Uber. Call an Uber here, you've got it.

Aaron Jun: And that change felt seismic, and it happened in a blink of an eye.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah.

Aaron Jun: I think we're going to see something very similar happen in healthcare, where all of the sudden it's going to feel really bad, really, really bad as it always has. You're going to feel stranded and alone.

And all the sudden, you blink your eyes, and it's all different.

Lilly Stairs: I think that is pretty much the perfect way to end this podcast.

Aaron Jun: Me too.

Lilly Stairs: All right. Well, thanks everyone for joining! I really hope that this helped demystify clinical trials a little bit for you, tackling some of these questions.

I'm sure we're going to end up doing some sort of follow up to this because we do have so many questions that we get.

Aaron Jun: Right.

Lilly Stairs: Please, do feel free to send us a question any time. Let us know if you have topics you want us to discuss on the podcast, we are happy to take recommendations.

Aaron Jun: And guides.clarahealth.com for any questions you have about clinical trials and the process. We've pretty much answered everything we know we have to answer. But, if we're missing something, go ahead and let us know.

Lilly Stairs: Call us and tell us, yes.

Aaron Jun: Lilly@clarahealth.com, Aaron@clarahealth.com.

Lilly Stairs: Lilly with two L's, Aaron with two A's.

Aaron Jun: A-Aron.

Lilly Stairs: Cheers.

Aaron Jun: Cheers.