Hi everyone and welcome to the Patients Have Power Podcast! It's a space where we're keeping it real about what it means to live life with chronic illness, and talking to incredible advocates who are redefining what it means to be a patient. I'm your host, Lilly Stairs, autoimmune patient and head of patient advocacy at Clara Health.

Lilly Stairs: Today's guest is Aaron Blocker. Aaron is brilliant and dedicated IBD and rare disease advocate. He's one of the original online IBD advocates who started his Facebook page, Support IBD, back in 2010. The page has since garnered over 25,000 followers.

In this episode, Aaron and I have a really interesting discussion surrounding his IBD, his very new rare disease diagnosis, and the way that his life as a patient has inspired him to purse a career in scientific research. Aaron and I were lucky enough to have time to sit down at the inaugural Crohn's and Colitis Conference in Las Vegas, and I hope that you enjoy the conversation as much as I did!

Below is a transcript of the episode for your reading pleasure.

Lilly Stairs: Hello everyone! We are here at the Crohn's and Colitis Conference in Las Vegas. I am very lucky to have Breakthrough Crew Ambassador and a good friend of mine, Aaron Blocker here with us today.

Aaron Blocker: Hi!

Lilly Stairs: Aaron is going to chat with us a little bit about his IBD experience, as well as his new rare disease diagnosis. Let's dive in with Aaron.

Can you just give me a little bit of background on when you were first diagnosed, what that journey was like, and then how you got into advocacy? Because you were really one of the first IBD advocates on the scene.

Aaron Blocker: Yeah, I was initially diagnosed back in 2009. I was 17 at the time - just started college. It was a long process of getting the diagnosis, you know. Years. The process was hard, and I was still technically a pediatric patient at that point, so it was a lot of... thrust into a world of being sick and obviously knowing what's going on, but getting the correct treatment at that point.

But that really was the biggest thing that got me into advocacy, was not actually knowing anybody with the disease. About eight months or so after my diagnosis, I started reaching out to people. Facebook was, as far as pages and blogs, a very new thing in the world, so I got into that.

Lucky to have got in when I did, and it's been a great experience and it's really built up more than I could ever have dreamed and I love doing it.

Lilly Stairs: I know, over 25,000 likes on Facebook - it's kind of crazy!

Aaron Blocker: Yeah it is. It's been a humbling experience to be able to reach that amount of people.

Lilly Stairs: Absolutely.

Aaron Blocker: And help a few people, hopefully.

Lilly Stairs: Especially when, in particularly, in IBD and autoimmune diseases, it is predominantly females who are diagnosed. Having male leaders like yourself, I think is really valuable.

Have you ever had any male patients who have reached out to you in particular to just say, thanks for advocating, or have you had any experience around that?

Aaron Blocker: We actually hear that a lot. There aren't many men who just wanna sit and talk about their disease, and obviously I think that has a lot to do with the male ego and seeming that you're not, I guess strong.

To me, it's more about just being open, and for me that's a coping mechanism, is to be open with people.

Aaron Blocker: There have been men who have reached out and people who we've talked to - even if it was private, behind the scenes, not actually being open about it. But it's been different.

You're right, there's not that many of us males who are really out in the advocacy world. We definitely need more, for sure.

Aaron Blocker: Everybody has their thing that they... not even everybody wants to talk about their disease so openly. It obviously seems like it's less males than females.

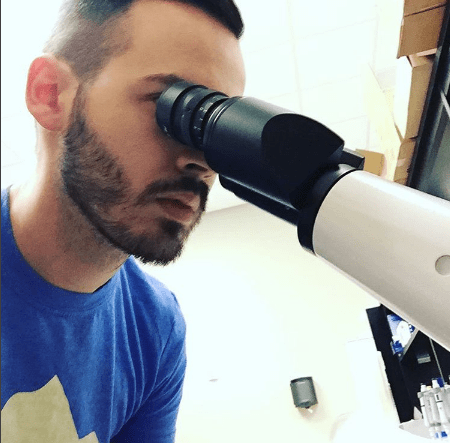

Lilly Stairs: I kind of wanted to talk a little bit about your experience pursuing a career in research, because now you are doing something that is deeply connected to your experience as a patient.

What has that been like, and what are your thoughts on patients getting involved in research and medicine, and all of that jazz?

Aaron Blocker: For me, even before the diagnosis (I was a few months into college), I had already started as a biology major, and medicine initially was what I wanted to do.

But then, being diagnosed with a disease, an autoimmune disease, a biological disease, for me, it helped me find the passion that I wanted to be in.

Yes, my interest was already in science, but the diagnosis drove me into a career of really understanding the process of disease and how this works on a cellular level.

Lilly Stairs: Sure.

Aaron Blocker: That's been a huge driving force for me. I think that we're seeing it more - there's value in patients who can get into science and medicine. Even just these careers where, it doesn't have to be science, of course, but it's very valuable, at least these days, because you understand what's going on, you're in the lab, you're doing this. You understand how this all works and then you can look at yourself as a patient.

Okay, this makes a lot of sense, especially, even for me, understanding how these drugs work and all that is important. I ended up not wanting to go to med school. To get into research, do a PhD, that's still my goal, to do that, but it's been a unique experience.

I do think it adds value to me, not as just a person but as an advocate as well.

Lilly Stairs: Sure. Where is the value that you see on the side of the employer and the research that you're doing, having that patient perspective? Has that been a value add there too?

Aaron Blocker: I think it definitely has. We get to do work with pharmaceutical companies, and all of these non profit corporations who want your opinion as a patient, but then you're like, I actually have a little more experience in something else. I have a career in something that could be valuable.

Actually working with them to even be able to explain these mechanisms of actions and all of this on a level that I, as a patient, and every other patient will understand, but also doing it in a way that meets multiple different needs of what to do.

Aaron Blocker: To me, it's like - most people who go into science and medicine, if they're sick, they don't want to talk about it. They think it'll be a hindrance to their career and that's always an option, but I think especially with anything, most people worry about their career with chronic illness.

But I think there's definitely a fine line of trying to figure out where patient advocacy ends and my science begins, and all of that. It's a new thing for me, but I'm hoping that in the end it works out and adds value to something bigger.

Lilly Stairs: Yeah, absolutely. And Aaron does a great job on his blog, breaking down some of those more scientific topics so that, really anyone can understand the way that medicines are working, the way that IBD works as a disease, so that's something that I recommend checking out!

Lilly Stairs: I want to take a moment to switch gears and talk a little bit about something that you've been going through this year, and what is a rare disease diagnosis.

Do you want to dig a little bit into that and share your experience thus far?

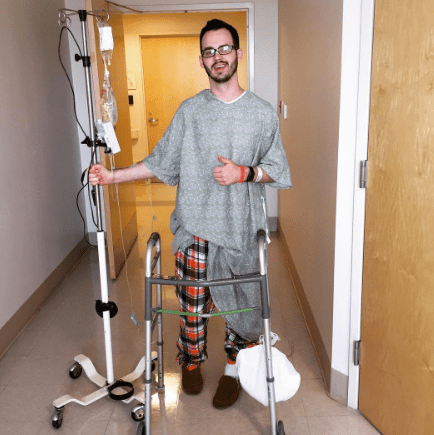

Aaron Blocker: It's been a very, very different experience from, going from having Crohn's disease and something that, fortunately is well known and there are multiple treatments. Crohn's disease has been a huge part of my life and has caused me a lot of trouble and hospitalizations and all that.

Aaron Blocker: But the rare disease diagnosis has been so different, because nobody knows about it. I live in a place where none of my doctors have ever seen it, they've never even had a case of it.

I've had to be referred out and there are only two or three specialists in the country who actually deal with it, specialize in it, and kind of know how to at least treat whatever's going on as best as you can.

It's very, very different from having Crohn's. Again, not to make light of having Crohn's, but it's so different when you're thrust into a disease that is extremely rare. It's 100 percent genetic driven, you've got a mutation in your gene and all that. It's very different. There's only one treatment available, and it's not available to everybody.

You have to deal with the fact that there's one treatment, it may or may not work, you may or may not can get it, and there's a lot of uncertainty going forward with that.

Aaron Blocker: I think that's true for most diseases that are extremely rare. Most of them don't have a treatment, and if they do, they only have one. It's been very different trying to navigate. It's been a long time since I've been a newly diagnosed patient, so having to revert back to how I dealt with dealing with Crohn's and then now going back to that new learning about my disease and what we can do and what to move forward.

It's been super different. It's very, very hard.

Lilly Stairs: What is the name of the disease again?

Aaron Blocker: It's called hypophosphatasia.

Lilly Stairs: And what are the biggest ways that's impacting you?

Aaron Blocker: For me, I have very, very severe skeletal issues. Four hip replacements and osteoporosis that they initially attributed to being malnourished and Crohn's disease and steroids. But it never made sense in the fact that I was on very little steroids. The first time I ever had a bone scan, my bones were just horrible.

Now I've had four hip replacements because my bones are too weak, and there are no drugs available. Any osteoporosis drug on the market you can't take because of the genetic disease.

Aaron Blocker: So that, and then finding out that I've got issues with my kidneys and could have hearing issues. It's been so much more of initially thinking, maybe it was bad bones and that's bad enough, but the fact that it's damaging other organs, and there is no treatment.

Lilly Stairs: And there's two things I kind of want to pull out of that, one of them being, you were told for most of your life that this was due to steroids.

Your experience with your bones was due to steroids, or it was due to being malnourished, and there was something beneath the surface and it didn't really add up. None of that added up, even when you were hearing it, you're hearing steroids, "but has it really affected other people as badly as it has me?"

Lilly Stairs: That story I think is important for a lot of patients to hear, because if there's something that you're not comfortable with, or something that doesn't add up quite right, it's okay to push back.

I think you've done quite a bit of that, pushing back to try to get a diagnosis and to figure out what was going on, because you knew that something was wrong, beyond what the doctors were initially telling you.

Aaron Blocker: The thing was, looking back, there were signs in my blood work. I was born with skeletal issues, bowed legs and stuff like that. There was stuff that was definitely missed growing up. I was born, again, with skeletal abnormalities and a lot of issues growing up that.

I wasn't diagnosed with Crohn's until I was 17. Sure, I was a little malnourished but I'd never been on steroids, but I'd broken a bunch of bones. There were multiple things that were missed.

Again, I don't blame my physicians for that, because the disease is so rare.

Aaron Blocker: I actually am the one who brought the disease up after looking through and doing my own research, actually looking to see what was going on. Because eventually, last year when my hips failed only after three years, I knew something was wrong.

I was right, we got the diagnosis.

Lilly Stairs: That's incredible, so you really self diagnosed a very rare disease. That is such a great example of why it is important to do your own research and why it is important to trust yourself and trust your body.

I've heard this time and time again of patients really self diagnosing, because we have these resources at our fingertips now. When you can just Google anything, you can talk to other patients who have been there.

I think that's really inspiring and I hope that people take that to heart because it's important to remember to trust yourself.

Lilly Stairs: The other thing I kind of wanted to address in this whole experience that you've been through is how difficult it must be to have only one treatment available. Something that not even every patient can access.

What are your thoughts on the future for this disease and what do you see needing to happen so that there can be more treatments on the market?

Aaron Blocker: From the knowledge that I've gained from just talking with my doctors and other patients, I think that there needs to be more studies. nd the agree, it's studies on people who are diagnosed later in life. And the treatment is available to people who can show that they had onset prior to being 18. So, I'm 25, but we can prove that I've had onset prior to that, so technically, we can try to get me on the drug.

I think there are other adult patients who were diagnosed later in life, and they probably had onset but can't prove it. I think there needs to be more research in that area and I hope that there will be. I assume that's probably something that's gonna happen, maybe not now but in the future.

Aaron Blocker: The resources for that are super limited. It's a very small patient group, it's a very ... and it's so rare, obviously there are people who are not diagnosed yet, we know that. I think the big thing is there has to be something for patients who can't, like me, find enough old records initially, or their bones are so bad and they've been through all this. There has to be some kind of way around that.

I think there just needs to be obviously more research, which is easier said than done.

Aaron Blocker: I think there has to be some sort of plan in place to evaluate those patients who have really severe disease, yet the drug requires you to have onset prior to being 18, but there are no other options.

You can't take osteoporosis drugs, you can't have surgery, you can't take calcium, you can't take vitamin D. There are multiple things you can't do, so I think there needs to be more effort pushed into having more, I guess, availability.

Lilly Stairs: If there were, or are clinical trials for that matter, for this disease, is that something you would consider participating in?

Aaron Blocker: Yeah, I've already talked to my doctors, if we can't get the drug approved or even if there's a new drug on the market, I'm 100% open to doing that.

In the end, it might be the only option for treatment, and I'm okay with that if that's what it comes to, because there has to be something.

Lilly Stairs: We've talked a little bit about that - you have this unique perspective on research and clinical trials because you understand it from the researcher point of view, not just the patient point of view.

What are your thoughts around the way that trials are run and safety of trials and how all of that works?

Aaron Blocker: I think people, from my own experience, even doing any sort of lab work that requires even animals, the lowest level animals still require a vet on staff, you have to have IRB approval. I've worked with animals where we had to let them incorporate for two weeks, so meaning just stay where they're kept on site and fed and nurtured and loved.

These are animals, I love animals, and animal research is a very important thing. But then to translate that into people, and clinical trials, it's so much more regulated when it comes to that.

Aaron Blocker: They're not just gonna poke you and prod you. They're not gonna make you suffer more than you already are. People don't understand that, they don't understand that there are boards, meetings, and doctors. All of these people before you can even get to trying something on a person. I think that is important.

I think you have to realize that there's gonna be safety issue with anything, even, we were talking earlier, even with drugs that are on the market, you could have some adverse reaction without knowing, even though it's already approved.

Read more about how clinical trials are regulated for safety here.

Aaron Blocker: Obviously you have to consider it, and you also have to consider that this clinical trial or whatever this study is might be your only option for treatment.

How hard are you willing to fight to get treatment?

Lilly Stairs: Right. And even if it's not your only option, is there something in the pipeline or in a trial that could be a better fit for you based on the way that you're presenting in your disease?

There's a lot of different things to consider, but it's always interesting for me to talk to people who are both patients and on the researcher side, because I think that there is a really unique perspective there. I appreciate all the advocacy that you've done in that area.

Lilly Stairs: I think that we're getting towards the end of this session. This has been really very informative and a unique perspective.

I'd like to end by asking you what 'patients have power' means to you?

Aaron Blocker: Like we talked about earlier, I played a huge part in getting this diagnosis. Again, you obviously have to be careful, you don't wanna push too far with something - know that your doctor is your doctor.

But also, if you think something's wrong, or there's something that you think that you might have, present them with this and ask them, "hey do you think this is something that it could be?"

Any good doctor will listen to you and evaluate that maybe this is something that we should look at.

For me, that was a huge thing. I presented this to them myself, I found it, I gave it to them, and they're like, "yeah, we think this is it." They agreed and we moved forward.

For me, without that, I probably still wouldn't be diagnosed, and that was two years ago.

Lilly Stairs: That's powerful. That's patients having power.

Aaron Blocker: Exactly.

Lilly Stairs: Thank you so much for joining us Aaron.

Aaron Blocker: Thanks for having me.

Lilly Stairs: Thank you all so much for joining us. We'll see you in two weeks for our next installment. In the meantime, be well and remember that you hold the power.

Aaron Blocker is an IBD advocate whose goal is to use his background in science, and experiences as a patient, to help educate and support other patients. Connect with him on his website and twitter @AaronBlockerIBD!