Clinical trials and the people who volunteer for them are vital in preventing, detecting, and treating disease. They can help us to learn more about the safety and effectiveness of new or existing treatments.

Only a small number of people take part in clinical trials, and those who do often don’t represent the U.S. population as a whole. Diversity is important in making sure we know all we can about a treatment’s benefits and risks, and the people enrolled in a clinical trial should represent the types of people who are likely to use the therapy.

Simbonika Spencer has worked in diversity, equity, and inclusion for 15 years. She’s currently the DEI manager for the weight loss app, Noom, and previously worked for the American Cancer Society (ACS). At ACS, she managed patient services and health education programs at the state level and worked to address health disparities, “which play a huge role in every aspect of cancer,” she said.

ACS is the largest non-profit funder of cancer research in the U.S. outside of the government. As part of their research activity, ACS matches researchers with people interested in participating in clinical trials. Although Spencer and her colleagues promoted the matching service, they encountered a lack of diversity in clinical trial participants.

Spencer’s experience is a microcosm of clinical trials nationwide. Each year, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) publishes a snapshot of clinical trial demographic data for new drugs to the U.S. market. The report’s goal is to show differences in the efficacy of certain medications and their side effects among different demographic groups.

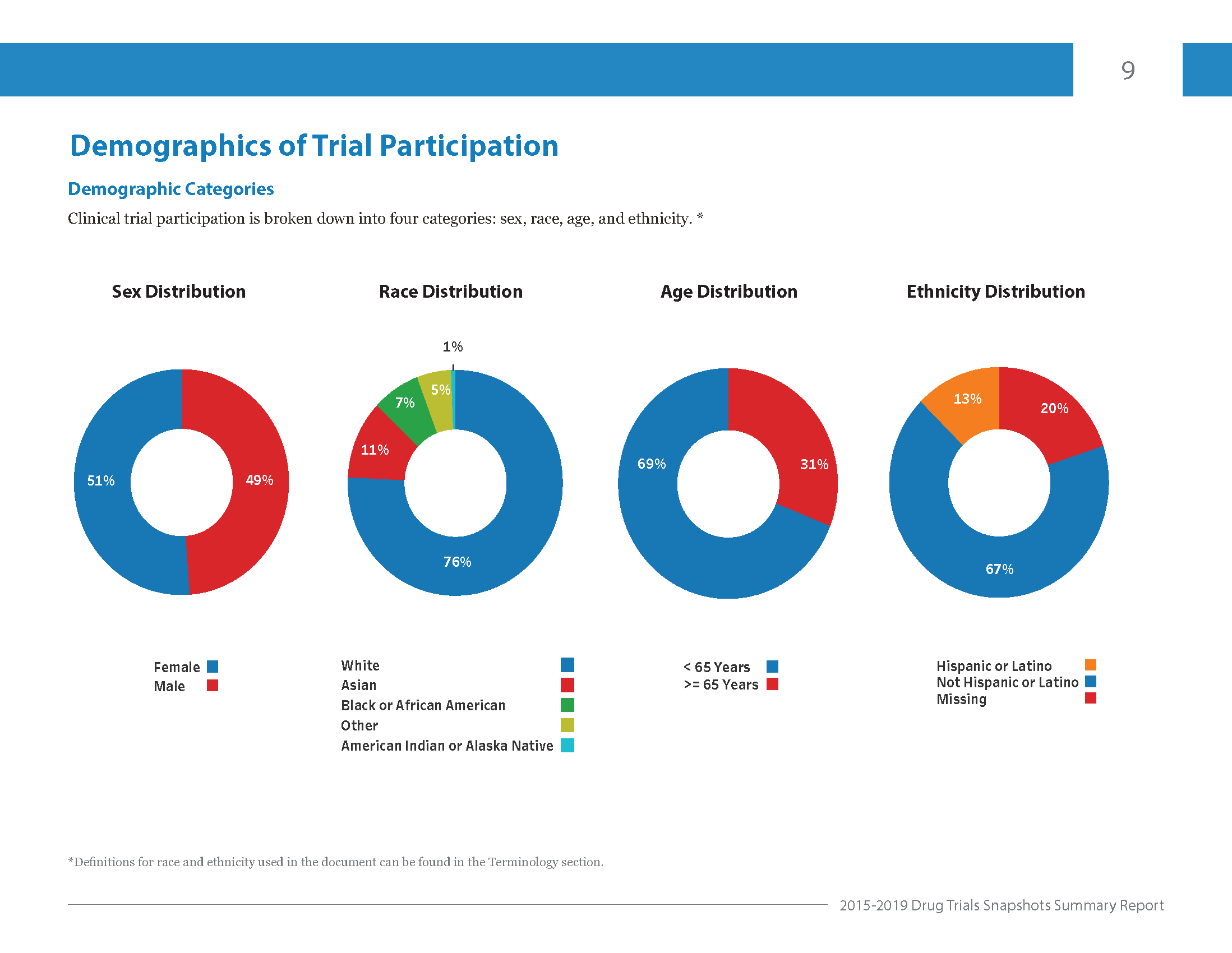

CDER’s report for 2015-2019 shows that although participants were evenly split by sex, there was less diversity across other groups like age, race, and ethnicity.

Image courtesy: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

All of these factors can affect how different people respond to the same treatment. Plus, specific groups are at a higher risk for certain diseases like heart disease and diabetes. It’s why a diverse clinical trial pool is critical.

When a group is more diverse, researchers can learn more about a treatment’s safety and how well it will work in diverse populations. In the long run, information on these differences can help doctors and patients make more informed treatment decisions.

Clinical Research History

Lack of diversity in clinical trials is an issue that has persisted for as long as there has been this type of research. The first clinical trial dates back to 1747, when James Lind, a Scottish doctor, studied scurvy treatments in sailors.

In 1993, Congress passed the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, which for the first time required that researchers include women and minorities in NIH-funded research.

Before then, researchers were encouraged, but not mandated, to engage women in clinical trials. And they rarely did. Women’s health was mostly limited to reproduction—family planning, maternal and child health, and abortion—while dismissing womens’ overall health.

Researchers also conducted unethical and misleading research like in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Six hundred Black men in Macon County, Alabama thought they were receiving free medical care for “bad blood,” a term they used for various illnesses, including syphilis. Instead, they unknowingly participated in a decades-long study of the disease’s progression. Dozens died without receiving treatment and passed the illness to their spouses and children at birth.

This long history of neglect and unethical treatment has created mistrust in marginalized communities, which still casts a shadow over clinical research today.

Recently, Spencer has talked to DEI colleagues about the COVID-19 vaccines. They’ve found that many in the Black community are hesitant to get immunized, or only want the vaccine from a specific drugmaker that included more Black participants in their clinical trial.

“There’s a lack of trust in healthcare across the board,” Spencer says. She’s seen mistrust among racial minorities, people with physical and mental disabilities, and in the LGBTQ community.

Language, cultural, and location barriers also contribute to a lack of awareness about clinical trials. Financial challenges such as study-related travel expenses can also prevent people from signing up for them.

The Future of Clinical Research

The issue of diversity in clinical research has only come to the forefront in the past 20 years. Today, companies like Pfizer have committed to removing barriers to clinical trial participation. And, the FDA is working with federal partners, medical product manufacturers, medical professionals, and health advocates to encourage diversity. They have tools and information on their website for potential participants and researchers, including a section that focuses on people of different ages, races, ethnicities, and genders.

The FDA also regulates clinical trials, and they’re supervised by the Institutional Review Board. These groups make sure clinical trial volunteers are safe, that researchers minimize the risks of testing a new medical treatment, and they’re conducting clinical trials ethically.

Spencer says people in marginalized communities want to see themselves reflected in the researchers carrying out clinical trials and suggests researchers create more diverse recruitment teams. Other ideas include:

- Clinical trial brochures in various languages and that feature different genders, races, ethnicities, and physical abilities

- Regular training for research teams to learn about engaging with people from diverse communities

- Clinical trial coordinators or principal investigators who are culturally similar to participants

- Researchers vetted by community organizations and leaders

- Collaborating with trusted physicians, particularly if they belong to the underrepresented group

Clara Health is working to do our part to create a more diverse and equitable clinical trials space. From building relationships with community-based organizations that serve marginalized populations to consulting with patients and caregivers from diverse backgrounds. We’re putting in the work and holding ourselves and our clients accountable.

Research teams must continue to be mindful about improving their relationships with marginalized communities, starting with building trust. “Trust is a critical commodity when your goal is to have a clinical trial that’s as thorough, robust, and efficacious as possible,” Spencer says, but adds, “It’s not something you can build overnight.”